- Hits: 814

THE BOOK OF EARTHS

By

EDNA KENTON

New York: William Morrow & Company

[1928, No renewal]

Systems of the Universe

WHEN THE GREEKS IN THE SIXTH CENTURY B.C. took up the study of the universe,

its systems multiplied. The order of the orbits of the heavenly bodies, above

all, their disorder, fascinated the Greek mind. Eclipses occurred, but how?

A Comet fled through the sky, and did not collide with a sister body--why? How

were the Earth, Sun, Moon, and all the stars supported in space? What are the

relative distances of the spaces between them? Which were the larger bodies?

the smaller? What were the divisions of Space? What were the major combinations

of the great elements? How were these combinations effected--and a hundred other

questions.

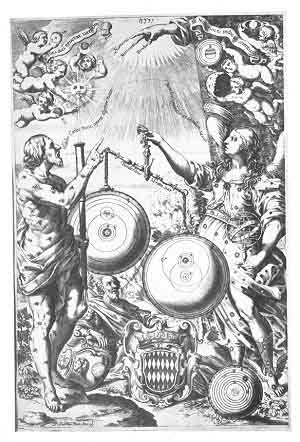

PLATE XXXII. (Frontispiece to Almagestum Novum; Ioannes

Riccioli, 1561)

Homer was the first poet of the Greek universe, but Thales was its first

philosopher (640-572 B.C.). He believed the Earth was a disc floating "like

a piece of wood or something of that kind," on the waters which were the origin

of all things, including fire and air as well as Earth; and his interest in

eclipses led him into a protracted study of the movements of the Sun and the

Moon and their relation to the Earth.

Anaximander (c. 611-545 B.C.) was his contemporary. He gave up the idea that

the water was the origin of everything, any more than any other substance known

to man. Everything originated "from the nature of the infinite," and to it returned.

Hence it followed that this world was not eternal, but merely one of a procession

of worlds. He described the figure of Earth as either flat or convex on the

surface, but much more like a cylinder or stone column than the thin disc of

Thales. Eventually he called it cylindrical, with a height equal to one-third

of its breadth. This cylinder, being in the centre of the universe, was stable,

in equilibrium, since it had the same relation to every part of- the universe.

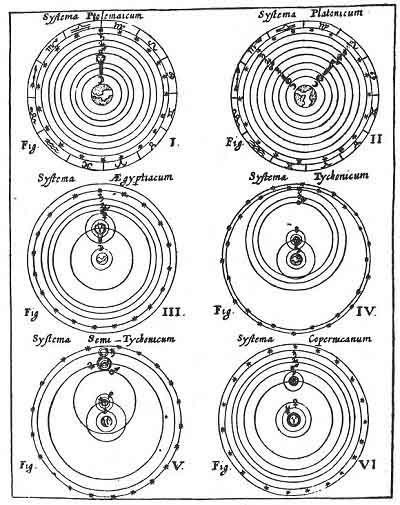

FIGURE 66. The Systems of the Universe.

(From Iter exstaticum ceste; Athanasius Kircher, 1660, Plate II.)

Above it were a series of heavens, the first of air, the second of all the

stars, the third of the Moon, above that the heaven of the Sun and above all

the heaven of the heavenly fire. He had an extremely complicated theory to account

for a motionless heaven and moving bodies; he appears to have imagined the Sun,

for instance, to be an enormous wheel filled with fire, its rim pierced by a

single hole the size of the Earth.

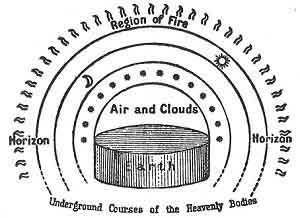

FIGURE 67. The Universe according to Anaximander

(c. 611-545 B.C.)

(From Dante and the Early Astronomers; M. A. Orr (Mrs. John Evershed),

1913.)So, too, the Moon and stars rolled through their heavens; eclipses came from

the holes in the Sun-wheel's rim and that of the Moon being partially or wholly

stopped up. Quite exactly, his Sun and Moon were vessels filled with fire.

Of course only the upper surface of Anaximander's Earth was habitable; below it the heavenly bodies had their underworld course; for the rest, the horizon marked the limits of the known and the knowable.

He seems to have held too the curious idea that the series of worlds which come out of the infinite and go back into it may be also called gods, since, like gods, they are created, they live, they die, and are again created.

For a hundred years following Anaximander's death, the Greeks were still asking how the Earth was held in balance, and why the heavenly bodies did not fall from their places in the sky and destroy the Earth. Empedocles and Anaxagoras offered this explanation--that a great whirl-wind swept continuously round the Earth, serving the double end of holding the heavenly bodies aloft and of driving them across the sky. Anaxagoras believed that this same whirlwind was responsible for the stars themselves; that they were fragments of the Earth, torn off by the violence of the whirlwind, and that their light came from no more than the heat produced by friction. He also believed that the "heaven of the stars" was far beyond that of the Sun.

As for Empedocles, he re-asserted that everything consists of the four elements,

Earth, air, fire, and water, either in a pure, or a combined, or a mixed state

merely; and he said further that all these combinations and mixings were brought

about by two forces alone, one attracting, and one repulsing, one Harmony, the

other Disharmony, one Cord, the other Discord. He had also a very individual

idea of the Moon and the Sun; the Moon is air rolled together with fire--it

is flat like a disc and gets its light from the Sun. But the Sun, he said, is

a reflection of the fire surrounding the Earth; it is not itself of a fiery

nature, but merely a reflection of fire, "like that which is produced in water."

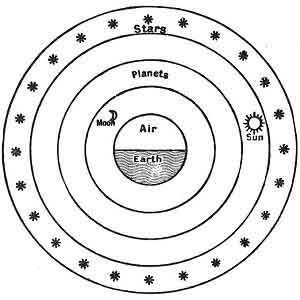

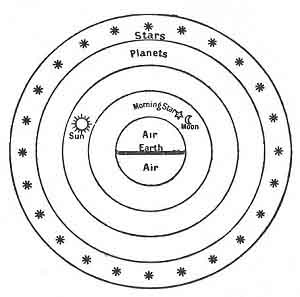

FIGURE 68. The Universe of Leucippus(c. 450 B.C.)

(From Dante and the Early Astronomers; M. A. Orr (Mrs. John Evershed),

1913.)Leucippus (c. 450 B.C.) changed Anaximander's figure of the universe considerably.

He still held that the Earth's flat upper surface was its only habitable area,

but he gave the whole mass of the Earth the shape of a tympanum or kettle drum,

flat, with a slightly raised rim--according to this idea man was living on the

flat top of the southern hemisphere. Above the hemisphere of Earth was the hemisphere

of air, the two surrounded by the crystal sphere which held the Moon. Above

the Moon's sphere was the planetary sphere; above this the sphere of the Sun,

with the star-zone last, "perhaps outside." He accounted for the inclination

of the axis to the horizon by saying that the Earth had sunk towards the south,

which is merely the other half of the ancient saying that the Earth is raised

towards the north.

FIGURE 69. The Universe of Democritus(c. 430 B.C.)

(From Dante and the Early Astronomers; M. A. Orr (Mrs. John Evershed),

1913.)Leucippus had a disciple, Democritus (c. 430 B.C.), who retained the thin

Earth-disc of Thales, but added to it the surrounding rim of his master's Earth-drum.

He changed Leucippus's Air-Earth sphere into a sphere of Air, divided horizontally

through its centre by the Earth-disc. Thus, like the cylindrical Earth of Anaximander,

it rested on nothing but air. Next the Air sphere he placed the Moon and the Morning Star, then the spheres of the Sun, the planets and the fixed stars.

The Sun, he said, was ignited stone or iron, and the Sun and Moon, each a large solid mass, were none the less smaller than the Earth. Originally, he said, the Sun and the Moon had been two Earths, like this of ours, and each of them, like ours, at the core and centre of a world. But these two worlds had encountered our world, which had absorbed them both, and had taken possession of the "Earth" of each. Comets, he said, are caused by two planets approaching each other closely. The Moon was not only a solid body, but, having once been the "Earth" of another world, it still has mountains and plains and chasms, which cause the markings on its face. Anaxagoras however had said this before him, and had also asserted that the Moon was still inhabited. Democritus also taught that the light of the Milky Way was caused by a great multitude of very faint stars. Later it was said that the Milky Way was a former path of the Sun, which for some obscure reason had changed its course.

It was Pythagoras who numbered and measured and named for the Greeks the

five great planets of our system, and who gave them places in the heavens equal

in importance to the greater heavenly bodies. And it was Pythagoras who taught

that the Earth was a perfect sphere, hanging, if not moving, freely in space,

with its whole surface habitable, and with men moving freely on all its sides.

For the Earth, he said, balanced in the centre of the world, cannot fall, nor

can it let anything which belongs to any part of it fall. There is no below,

there is no above, for our North is South to the men of the antipodes; there

is nothing but the Centre, where we are, and it is illusion to believe otherwise.

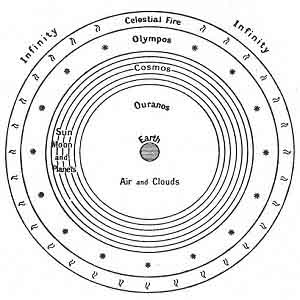

FIGURE 70. The Universe of Pythagoras(c. 540 B.C.)

(From Dante and the Early Astronomers; M. A. Orr (Mrs. John Evershed),

1913.)Number played the principal part in the universe of the Pythagoreans, for,

said they, everything in nature is governed by number, since number is the beginning

and the end of all relations. There are cosmic principles, they declared, and

these cosmic principles are mathematical principles, which are living principles;

numbers are the essence of the universe, the very substance of things, the cause

and effect of all that is in nature.

Pythagoras separated the planets and affirmed that their distances are in exact proportion to the intervals between musical notes. Combined with the Sun and Moon into a running scale, they make up the sacred number seven, and these seven notes of the cosmic scale constitute, with the mysterious star-sphere, the cosmic octave. As each of the heavenly bodies moves in its path, different to, yet harmonious with all the others, it sounds its own individual note in the great octave that is "the music of the spheres." This music, said the Pythagoreans, is all about us and has been since our infancy, but we live beside it "as one lives beside the cataracts of the Nile"--we never know we hear it.

According to Aristotle, the Pythagorean universe was divided thus:

The Earth was, first of all, a sphere situated in the centre of the universe, and was surrounded by many spheres.

Ouranos or Sky stretched between the Earth and the Moon. It was the region of illusion and change, always filled with whorls of air and shifting clouds.

Cosmos was the region of "the celestial octave," the appointed place for the Sun, the Moon, and the planets. It consisted of seven concentric rings or spheres, in which these heavenly bodies, or "divine beings," lived their conscious, joyous lives.

Olympos was the Star-sphere, the pure-elemental region which completed the cosmic octave.

Beyond Olympos stretched the region of celestial fire.

Beyond the region of celestial fire was Apeiron, Infinite Air, Infinite Space,

from which and into which the Cosmos breathes, and through which and by which

only it lives.

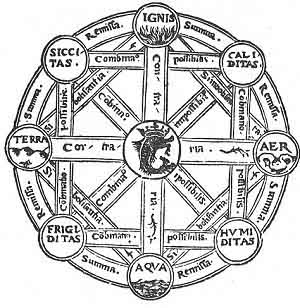

FIGURE 75. The Five Great Elements.

(From Spha Mundi; Orantius Fineus, 1542.)The Pythagoreans did not fail to take into account the five great elements,

from which they believed all things were fashioned. They fitted these five "Causal

Beings" into the five regular solids (Figs. 2-6

and ), to whose forms, they said, the component particles of the different elements

correspond. The component particle of Earth, for instance, corresponds to the

cube; of water, to the icosahedron; of air, to the octahedron; of fire, to the

tetrahedron; of ether, to the dodecahedron--the form which had been God's model

for the whole universe.

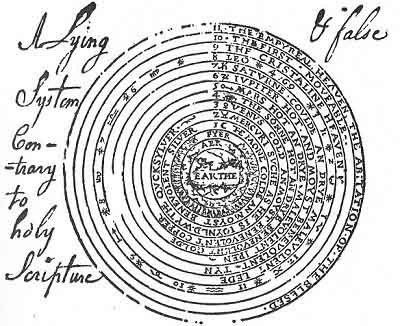

FIGURE 72. ''A Figure of the whole world, wherein are set

forth the two essentiall Parts, the eleven heavens, and the foure Elements."A Figure of the Whole World" (Fig. 72 ) is the

Pythagorean-Ptolemaic system, much elaborated. It begins by taking into account

the "foure Elements," but it extends the number of the imaginable heavens beyond

the "cristaline" to two--this was an invention of the medial astronomers.

These two additional heavens were the Primum Mobile, or the "First

Movable," and "The empyreal heaven, the habitation of the blesed."

Click to enlarge

FIGURE 73. System of the diverse spheres.

(From Cosmographia; Petrus Apianus, 1660.)

This last was the Heaven of Heavens, motionless, incorruptible, the place of the eternal mysteries. None of these spheres consisted, of course, of any materially palpable substance; they were great spherical zones of aethereal space, arranged one within the other, which circled about the motionless Earth at differing rates of speed. Perhaps, instead of "spheres," or "shells," or "zones," these moving regions are better expressed by the term "velocities."

Fig. 73 represents again the same system, even more elaborately inscribed with "correspondences." By aid of these two guides through the "two essentiall Parts" of the whole world--that is to say the eleven heavens and the four elements, the six systems of the universe shown in Fig. 66 can be more or less easily followed.

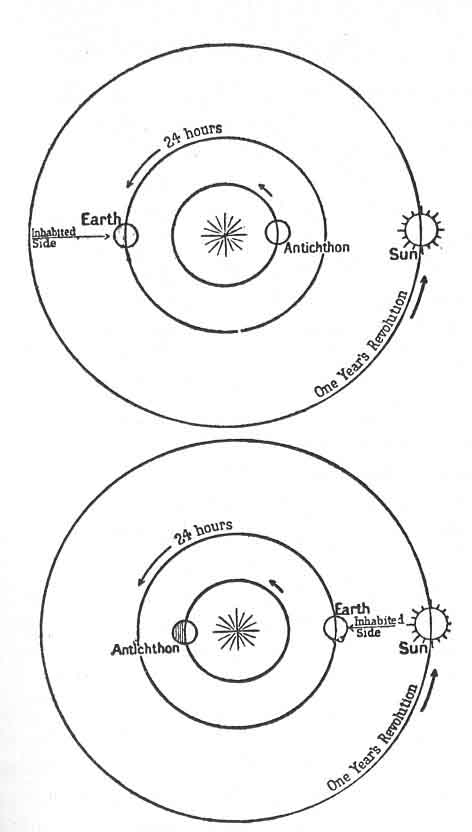

ONE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PYTHAGOREAN SYSTEM might be mentioned here--the attempt of an otherwise unknown astronomer, Philolaus, to remove the motionless Earth from its place in the centre of the universe and give it an orbit of its own. His reasons, except that he hoped by this to account better for the seemingly contrary movements of the heavens, do not concern us here. But it is a transition-picture. For by moving the Earth from the centre and letting her move in Space, he may have solved one problem, but he raised two new ones. He had left the sacred place, the Centre of the World, empty, and he had disturbed the cosmic octave by adding to it another moving body. Heretofore the Earth had been mute because it was motionless; now movement gave it its own note in a disturbed scale. So in the sacred place he put the purest of the elements, Fire, forerunner of the Central Sun. Then, more to restore the harmony of number, quite likely, than to explain Night and Day, he created another moving heavenly body, the planet Antichthon, or Counter-Earth, and gave it an orbit between the Earth and the Central Fire with one of its faces turned always to the Fire. This gave nine moving bodies, and with the star-sphere as another, the number was increased from the sacred number seven to the sacred number ten. The Earth revolved with one face turned always away from the centre; Antichthon, the new planet, was therefore always invisible. After this rearrangement was completed, explanations purporting to reconcile a geocentric with an ignicentric system were invented plenteously, some of them very interesting ones. "Those who partook of a greater knowledge," wrote Simplicius, "called the fire in the middle the creating power, which from the middle gives life to the whole Earth and again warms that which has been cooled. . . . But they called the Earth a star because it also is an instrument of time, for it is the cause of days and nights, for it makes day to the part illumined by the Sun, but night to the part which is in the cone of the shadow." And he ends by saying that the moon was called the antichthon, because it is "an aethereal Earth."

Some modern students of this confusion have suggested that the Earth and

the Counter-Earth or Antichthon might have been intended to be the two halves

of a single sphere, cut through a meridian and separated very slightly, with

the flat sides toward each other, but with the convex side of Antichthon turned

always towards the Central Fire, and the convex side of the Earth turned always

away from it. This may be so, but no one knows. For the Pythagorean teachings

were at the best obscure, and the Pythagorean text that has come down is scanty

and corrupt.

FIGURE 74. The System of Philolaus.

(From Dante and the Early Astronomers; M. A. Orr (Mrs. John Evershed),

1913.)Upper figure: Night on Earth. Only the side turned away from

the centre is inhabited; consequently the Central Fire and Antichthon are invisible.

Lower figure: Twelve hours later; Day on Earth. Earth has made half a revolution, and her outer side is now lighted by the sun, which has only moved about half a degree forward in its yearly orbit. Antichthon has also made half a revolution, therefore remains invisible.One Pythagorean, Hicatus of Syracuse, is said to have believed and taught that the heavens, the Sun, Moon, stars, and all the heavenly bodies are standing still, and that nothing in the universe is moving except the Earth, which, while it turns and twists itself with the greatest velocity round its axis, produces all the same phenomena as if the heavens were moving and the Earth were standing still."

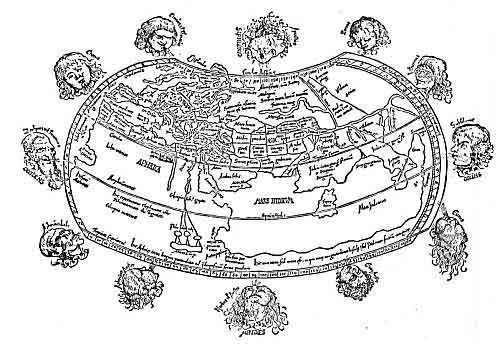

As above, so below! Philolaus placed the planet Antichthon or Counter-Earth

in the heavens, perhaps five hundred years before the Christian era. In the

first century A.D. Pomponius Mela, a Latin cosmographer, convinced that a spherical

Earth must have a more or less balanced distribution of land and water, drew

the first map on which the mysterious continent of Earth appears in the unknown

half of Earth--our antipodes. This continent he inscribed with the name Antichthones,

the Unknown. His pen had leaped over the impassable equatorial zone, and had

drawn below it a solid, bowl-shaped mass of land which no man had seen, and

which no man might ever see. And yet it must be there! It had been long known

through travellers that from Greece or from Italy the eastwardly land stretched

much farther than the land to the west, and it was therefore quite possible,

with no proof of the existence of a great western ocean, that the northern continent

of Europe-Asia-Africa might wrap around the sphere until its eastern edge touched

the western shore of the known Atlantic. But it was implicitly believed that

the known land stopped at the equator; the balancing continent must be therefore

at the antipodes.

FIGURE 75. Pomponius Mela's Map of the World, with Antichthones

(1st century A.D.)

(From De situ Orbis; Pomponius Mela, 1536.)When Pomponius Mela dropped his second continent to the south, he was a mistaken

man, but his Antichthones lingered in the imagination of men--lingered for nearly

fifteen hundred years, until Columbus, sailing west--to India--came upon the

West Indies and the Americas. The great astronomer and geographer, Claudius

Ptolemy, lived in the century after Pomponius Mela. There is a legend that he

was a descendant of the Egyptian kings, and knew their secret science of the

heavens; certainly he brought about a revival of mathematical geography that

had not been in the world since the great Alexandrian period, and he drew his

maps upon a form that was to be the model of the Earth up to and through the

Middle Ages.

Ptolemy believed the Earth to be a globular body, but the form on which his

maps were modelled was one slightly depressed at the north, and sharply cut

off a little below the equatorial line by a supposedly continuous Southern Ocean

which circled the equator and flowed below it. His historians do not seem to

doubt that his knowledge of the regions of the Earth extended as far as the

equator, and that he himself knew this fabled zone of fire was both habitable

and inhabited. But he confined himself to a map-form that included neither the

unknown Polar regions nor the hemisphere of Antichthones.