Clay Tablets from Sumer, Babylon and Assyria

This page is added because a lot of my readers complained about the absence of pictures of the published texts so I gathered some pictures of clay tablets from the internet, most of them are mentioned in my book as well as in the ancient texts in my Babylon and Sumer section.

To enlarge the pictures click on them

Special Thanks to The Schoyen Collection, worth a visit.

The Schen Collection comprises most types of manuscripts from the whole world spanning over 5000 years. It is the largest private manuscript collection formed in the 20th century. The whole collection, MSS 1-5268, comprises 13,497 manuscript items, including 2,174 volumes. 6,850 manuscript items are from the ancient period, 3300 BC - 500 AD; 3,864 are from the medieval period, 500 - 1500; and 2,783 are post-medieval. Never before there has been formed a collection with such variety geographically, linguistically, textually, and of scripts, writing materials, etc., over such a great span of time as 5 millennia.

The Schen Collection is located mainly in Oslo and London. Scholars are always welcome, and are strongly encouraged to do research and to publish material. Parts of the collection are deposited with universities and public libraries to facilitate access for scholars. Over 90 % of the MSS are unpublished at present.

Sumerian history

MS 2426 Sumer, ca. 2385 BCMS 4556 Sumer, ca. 2217-2193 BCMS 2814 Sumer, 2100-1800 BCMS 2855 Babylonia, 2000-1800 BCMS 2110/1 Babylonia 1900-1700 BCMS 5103 Babylonia 1900-1700 BC

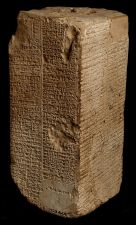

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF GISHAKIDU OF UMMA: WHEN SHARA SAID TO ENLIL, AND STOOD AT HIS SERVICE, GISHAKIDU, THE BELOVED OF SHARA - HERO AND FIERCE ENCHANTER OF SUMER, THE BOLD ONE WHO TURNS BACK THE LANDS, THE CONQUEROR OF NIN-URRA, THE MOTHERLY COUNSELLOR OF ENKI, THE BELOVED COMPANION OF ISHTARAN, THE MIGHTY FARMER OF ENLIL, THE KING CHOSEN BY INANNA; HE DUG THE CANALS, HE SET UP THE STELES -

MS in Sumerian on limestone, Umma, Sumer, ca. 2385 BC, 1/3 of a truncated cone, h. 11,9 cm, originally ca. 35 cm, diam. 5,3-7,3 cm, 2 columns, compartments with 30 lines in a transitional linear script between pictographic and cuneiform script.

Context: Continuation of the text (mainly listing the boundaries of Shara of Umma) on British Museum terracotta vase, former Erlenmeyer Collection (Christie's 13.12.1988:60), and also related to The Louvre AO 19225, a gold beard from a statue which alludes to the existence of King Gishakidu.

For another foundation inscription of Gishakidu of Umma, see MS 4983.

Commentary: The cone and the vase relate to the Umma-Lagash border conflict that lasted over the reign of many kings between ca. 2450 and 2300 BC, with many bloody battles. This conflict is the earliest well documented piece of history. All the written and artistic materials came from Lagash, such as the stele of the vultures in The Louvre. The cone and the vase for the first time tell the history from Umma's point of view. The present MS also reveals the unknown king of the British Museum vase, and dates it to ca. 2385 BC.

Information kindly given by Mark Wilson who will publish the text.

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF KING SHAR-KALI-SHARRI OF AKKAD, DESCRIBING HIS CAMPAIGNS AND CONQUESTS

MS in Sumerian on light green translucent alabaster, Akkad, Sumer, ca. 2217-2193 BC, 1 partial tablet, 10,0x11,5x4,7 cm, (originally at least ca. 20x25x5 cm), 2+2 columns (originally 5+5 columns), 18 compartments remaining in a formal archaizing cuneiform script of high quality.

Commentary: This was originally a luxury inscription of impressive size and beauty. No royal inscriptions have so far been published of this king, who is known from other sources, including monumental inscriptions. The king's name have been recut, after another name had been erased, possibly of the previous king, Naram-S (2254-2218 BC).

ROYAL INSCRIPTION COMMEMORATING DEFEAT OF MAGAN, MELUKHAM, ELAM(?), AND AMURRU, AND ESTABLISHMENT OF REGULAR OFFERINGS TO HIS STATUE; SCHOOL TEXT?

MS in Neo Sumerian and Old Babylonian on clay, Sumer, 2100-1800 BC, 1 tablet, 14,8x14,0x3,3 cm (originally ca. 16x14x3 cm), 3+3 columns, 103 lines in cuneiform script.

Commentary: The text was copied from a Sargonic royal inscription on a statue in the Ur III or early Old Babylonian period. Magan was at Oman and at the Iranian side of the Gulf. Meluhha or Melukham was the Indus Valley civilisation (ca. 2500-1800 BC). This is one of fairly few references to the Indus civilisation on tablets. The 3 best known references are: 1. Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BC) referring to ships from Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun; 2. Naram-Sin (2254-2218 BC) referring to rebels to his rule, listing the rebellious kings, including '(..)ibra, man of Melukha'; and 3. Gudea of Lagash (2144-2124 BC) referring to Meluhhans that came from their country and sold gold dust, carnelian, etc. There are further references in literary texts. After ca. 1760 BC Melukha is not mentioned any more. For Indus MSS in The Schen Collection, see MS 2645 (actually linking the Old Acadian and Indus civilisations), MSS 4602, 4617, 4619, 5059, 5061, 5062 and 5065.

Exhibited: Tigris 25th anniversary exhibition. The Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo, 30.1. - 15.9.2003.

LIST OF KINGS AND CITIES FROM BEFORE THE FLOOD

IN ERIDU: ALULIM RULED AS KING 28,800 YEARS. ELALGAR RULED 43,200 YEARS. ERIDU WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO BAD-TIBIRA. AMMILU'ANNA THE KING RULED 36,000 YEARS. ENMEGALANNA RULED 28,800 YEARS. DUMUZI RULED 28,800 YEARS. BAD-TIBIRA WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO LARAK. EN-SIPA-ZI-ANNA RULED 13,800 YEARS. LARAK WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO SIPPAR. MEDURANKI RULED 7,200 YEARS. SIPPAR WAS ABANDONED. KINGSHIP WAS TAKEN TO SHURUPPAK. UBUR-TUTU RULED 36,000 YEARS. TOTAL: 8 KINGS, THEIR YEARS: 222,600

MS in Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 2000-1800 BC, 1 tablet, 8,1x6,5x2,7 cm, single column, 26 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: 5 other copies of the Antediluvian king list are known only: MS 3175, 2 in Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, one is similar to this list, containing 10 kings and 6 cities, the other is a big clay cylinder of the Sumerian king list, on which the kings before the flood form the first section, and has the same 8 kings in the same 5 cities as the present.

A 4th copy is in Berkeley: Museum of the University of California, and is a school tablet. A 5th tablet, a small fragment, is in Istanbul.

Commentary: The list provides the beginnings of Sumerian and the worlds history as the Sumerians knew it. The cities listed were all very old sites, and the names of the kings are names of old types within Sumerian name-giving. Thus it is possible that correct traditions are contained, though the sequence given need not be correct. The city dynasties may have overlapped. It is generally held that the Antediluvian king list is reflected in Genesis 5, which lists the 10 patriarchs from Adam to Noah, all living from 365 years (Enoch) to 969 years (Methuselah), altogether 8,575 years. It is possible that the 222,600 years of the king list reflects a more realistic understanding of the huge span of time from Creation to the Flood, and the lengths of the dynasties involved. The first of the 5 cities mentioned , Eridu, is Uruk, in the area where the myths places the Garden of Eden, while the last city, Shuruppak, is the city of Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah.

- DEBATE BETWEEN BIRD AND FISH; PART OF THE SUMERIAN CREATION STORY

- CREATION OF THE WORLD, THE MAN AND THE HOE, 1 - 33, SUMERIAN MYTH

MS in Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 1900-1700 BC, 1 tablet, 24x17x5 cm, 2+2 columns, 42 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: Creation of the hoe is the text on MSS 2423/1-5, 2110/1, text 2, and 3293. Bird and Fish is also the text on MSS 2884 and 3325. About 50-60 sources for the Creation of the Hoe is known.

Commentary:

Text 1, a part of the Sumerian creation story; as a literary debate between the bird and the fish in which they argue for their usefulness in the universe as it was then conceived. It has a substantially variant form of the published text, and the end is unpublished. Parts of the text are similar to Genesis 1:20-22.

Text 2: The Sumerians believed that the hoe, one of their basic agricultural tools, in the beginning was given as a gift of the gods. A myth was created explaining the circumstances of this event. It opens with the Sumerian creation of the world and of man. There are parallels to both the Bible's 1st creation story: 'The Lord hastened to separate heaven from earth' (Gen. 1:6-10); 'and Daylight shone forth' (Gen. 1:3-5); and the 2nd creation story: 'The Lord put the (first) human in the brick mould, and Enlil's people emerged from the ground' (Gen. 2:7).

Exhibited: Tigris 25th anniversary exhibition. The Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo, 30.1. - 15.9.2003.

ICREATION OF THE WORLD, SUMERIAN MYTH: IN DISTANT DAYS, IN THOSE DAYS, AFTER DESTINIES HAD BEEN DECREED, AFTER AN AND ENLIL HAD SET UP THE REGULATIONS FOR HEAVEN AND EARTH, ENKI, THE EXALTED KNOWING GOD, LIKE A HIGH PRIEST WITH WIDE KNOWLEDGE, ENLIL-BANDA, IN THE LANDS WAS THEIR RULER. BY THE RULES FOR HEAVEN AND EARTH, THE FIXED RULES, HE SET UP CITIES. - HE DUG THE TIGRIS AND THE EUPHRATES. THEREUPON HE ESTABLISHED THE RULES OF THE LANDS. HE SET UP HAND-WASHING RITES, HE SET UP LIBATIONS

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 1900-1700 BC, 1 tablet, 10,6x5,0x2,2 cm, single column, 26 lines in cuneiform script, the lines on reverse missing.

Commentary: The present text is unique, and different from the abbreviated creation story which introduces the creation of the hoe (MSS 2423/1-5, 2110/1, text 2, and 3293), and some Neo Babylonian epic of Creation, Enuma Elish, 1000 years later.

Babylonian history

MS 1686 Babylonia, 1813-1812 BCMS 1876/1 Babylonia, 1792-1750 BCMS 1955/1 Syria, 1250-1240 BCMS 2063 Babylon, 604-562 BC

THE UR-ISIN KING LIST

- LIST OF THE 5 KINGS OF THE UR III DYNASTY WITH REGNAL YEARS FROM KING UR-NAMMU 2112 BC TO KING IBBI-SIN 2004 BC

- LIST OF THE 15 KINGS OF THE ISIN I DYNASTY WITH REGNAL YEARS FROM KING ISHBI-ERRA 2017 BC TO THE 4TH YEAR OF KING DAMIQ-ILISHU 1813 BC

MS in Old Babylonian with a few names in Sumerian on clay, Isin, Babylonia, 1813 or 1812 BC, 1 tablet, 5,6x3,9x2,0 cm, 21 lines in Old Babylonian cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1993, red quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: An incomplete tablet with the same texts was Erlenmeyer Collection no. 115, now in a public institution. The texts were originally extracted from date lists, now lost.

Commentary: 17 different Babylonian and Assyrian King Lists have survived, mostly in fragmentary or worn condition. The present King List is the only one perfectly preserved and is the oldest as well. All others are in public collections. In addition there are 23 surviving Sumerian King Lists, all in public collections except MS 2855 . The importance of the King Lists for the chronology of the Babylonian and Assyrian Kingdoms can hardly be over-estimated. They are crucial tools and primary historical evidence for the historians.

Published: E. Sollberger: 'New Lists of the Kings of Ur and Isin', in: Journal of Cuneiform Studies 8(1954) pp. 135-6; and A.H. Grayson, King List 2 in the article 'Kiglisten und Chroniken' in Reallexicon der Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archaeologie, Berlin 1980, p. 90.

Exhibited: 1. Conference of European National Librarians, Oslo. Sept. 1994; 2. 'The Story of Time', Queen's House at the National Maritime Museum and The Royal Observatory, Greenwich, Dec. 1999 - Sept. 2000.

HAMMURABI, MIGHTY KING, KING OF BABYLON, KING OF THE FOUR QUARTERS OF THE WORLD, THE BUILDER OF THE TEMPLE EZI-KALAM-MA ('HOUSE - THE LIFE OF THE LAND'), TEMPLE OF THE GODDESS INNANA IN ZABALA

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Zabala, Babylonia, 1792-1750 BC, 1 brick, 13x29x9 cm, originally ca. 33x29x9 cm, 9 columns, (7x16 cm) in cuneiform script.

Context: There are 10 bricks extant apart from MS 1876/1-2, 9 in the Iraq Museum and 1, former MS 1876/3, now in British Museum (gift from The Schen Collection). MS 3028 is a royal inscription on black stone from the shoulder of a statue.

Commentary: Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC), the great king who created the Old Babylonian empire, is today mostly remembered for his famous law code. But he also built a series of great temples like the present one in Zabala. Towards the end of his reign, Hammurabi ordered his law code to be carved on stelae which were placed in the temples bearing witness that the king had performed his important function of 'king of justice' satisfactorily. The famous stele now in the Louvre, was originally erected in the Sippar temple. The 12 surviving bricks are the only witnesses of the Zabala temple, its law code stele is lost.

For The Hammurabi law code, see MS 2813.

The Iraq bricks are published in: The Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia, early periods, vol. 4: Douglas Frayne, Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 BC), p. 352.

INTERNATIONAL JUDGEMENT MADE BEFORE INITESHSHUB, KING OF CARCHEMISH AND SHAUSHGAMUWA KING OF AMURRU WHICH WAS SENT TO AMISTAMRU II, KING OF UGARIT CONCERNInG PIDDU, THE FORMER QUEEN OF UGARIT, SISTER OF SHAUSHGAMUWA, AND FORMER WIFE OF AMISTAMRU. PIDDU IS EXILED BUT PROTECTED FROM BEING PUT TO DEATH IN THAT AMISTAMRU CANNOT BRING HER BACK TO UGARIT FOR ANY REASON, AND SHAUSHGAMUWA IS FORBIDDEN TO ASSOCIATE WITH HER OR MAKE PLANS THAT WILL HAVE ANY IMPLICATIONS ON THE ROYAL LINE AT UGARIT

MS in Acadian on clay, Carchemish, Syria, 1250-1240 BC, 1 tablet, 8,2x10,2x3,2 cm, single column, 15+5 lines in cuneiform script, with seal impression rolled across the whole of the tablet, showing the deity Sharruma advancing left, holding a double axe and a sceptre.

Context: The present tablet is one out of 11 tablets concerning the divorce and judgement of Queen Piddu, involving 3 of the Kingdoms of the time, as well as the Hittite empire under King Tudkhaliash IV (ca. 1265-1220 BC).

Commentary: The kingdoms of Ugarit, Amurru and Carchemish at the North-east corner of the Mediterranean, were squeezed between the 3 great powers of the 13th c. BC, the Hittite empire, Assyria and Egypt. The present tablet illustrates the tensions among the kingdoms that fills in a bit of the picture of the upheaval to come at the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age, leading to the fall of the Hittite empire to Assyria and the following Trojan war as described by Homer.

Published in Analecta Orientalia, 48, Roma, Pontificium Institutum Biblicum, 1971: Loren R. Fisher, editor, The Claremont Ras Shamra Tablets, pp. 11-21. The seal is published in Ugaritica III, p. 24.

Exhibited: 1. The Claremont Ras Shamra Tablets, at the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, Claremont, California, 1970-1994. 2. 'Preservation for access: Originals and copies'. On the occasion of the 1st International Memory of the World Conference, organized by the Norwegian Commission for UNESCO and the National Library of Norway, at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, 3 June - 14 July 1996.

THE TOWER OF BABEL STELE

ETEMENANKI: ZIKKURAT BABIBLI: 'THE HOUSE, THE FOUNDATION OF HEAVEN AND EARTH, ZIGGURAT IN BABYLON'. CAPTION IDENTIFYING THE GREAT ZIGGURAT OF BABYLON, THE TOWER OF BABEL. THE ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF NEBUCHADNEZZAR CONTINUES: ETEMENANKI, I MADE IT THE WONDER OF THE PEOPLE OF THE WORLD, I RAISED ITS TOP TO THE HEAVEN, MADE DOORS FOR THE GATES, AND I COVERED IT WITH BITUMEN AND BRICKS

MS in Neo Babylonian on black stone, Babylon, 604-562 BC, the upper half of a stele with rounded top, 47x25x11 cm, originally ca. 80-100x25x11 cm, 3+24 lines in cuneiform script, to the left: carving of the Tower of Babel from a side view, clearly showing the relative proportions of the 7 steps and the buttress construction and a temple complex at its foot; to the right: the standing figure of Nebuchadnezzar II with his royal conical hat, holding a spear in his left hand and a scroll with the rebuilding plans of the Tower in his outstretched right hand; at the top: a line drawing of the ground plan of the temple on the top, showing both the outer walls and the inner arrangement of rooms, including the one that once had a fine large coach in it, richly covered, and a gold table beside it, according to Herodot: The Histories I:181; on the left edge: a line drawing of the ground plan of Esagila, the temple of Marduk, showing the buttresses as an integral part of the construction.

Context: The lower part of the stele with account of further building works on other temples, was in a religious institution in U.S.A. The stele was found in a special hiding chamber, broken into 3 parts in antiquity, at Robert Koldewey's excavations of the site of the Tower of Babel in 1917. Its importance was immediately recognised. A photograph was taken with 3 archaeologists standing next to the stele. With the imminent danger of war breaking out in the area, they decided to rescue it, and each archaeologist carried one part out of the war zone. Two parts were taken to Germany, the third part to U.S.A. Now the 2 most important parts are reunited in The Schen collection. For bricks from the Tower of Babel, stamped with Nebuchadnezzar's name, used during the rebuilding, see MS 1815/1-3. For the only other known architect's plan of a known temple, see MS 3031.

Commentary: The Ziggurat in Babylon was restored and enlarged by Nebuchadnezzar II, King of Babylon 604-562, captured by Kyros 538 BC, Dareios I 519 BC, Xerxes ca. 483 BC, and entirely destroyed by Alexander I the Great 331 BC. Until now our knowledge of the Tower of Babel has been based on the account in Genesis 11:1-9, and of Herodot: The Histories I:178 - 182, with the measurement of the first 2 steps, and a Seleucid tablet of 229 BC (Louvre AO 6555), giving the sizes of the steps. However, no contemporary illustrations have been known, resulting in a long series of fanciful paintings throughout the art history until present. Here we have for the first time an illustration contemporary with Nebuchadnezzar II's restoring and enlargement of the Tower of Babel, and with a caption making the identity absolutely sure. We also have the building plans, as well as a short account of the reconstruction process. Only 4 of 24 lines concerning this has so far been read. The last of these lines also covers the restoration of the E-ir-inimanki ziggurat in Borsippa, once believed by some scholars to be the Tower of Babel. A German scholar identified a few worn wedges to represent the name of Nebuchadnezzar II; and Dr. Stefan Maul has recently confirmed the reading.

Exhibited: Rounded top part only: 1. The Bibliophile Society of Norway's 75th anniversary. Bibliofilklubben 75 . Jubileumsutstilling Bok og Samler, Universitetsbliblioteket 27.2 - 26.4.1997; 2. XVI Congress of the International Organization for the study of the Old Testament. Faculty of Law Library, University of Oslo, 29 July - 7 August 1998; 3. Tigris 25th anniversary exhibition. The Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo, 30.1. - 15.9.2003.

Published: To be published by Andrew George in the series, Manuscripts in The Schen Collection, ed. Jens Braarvig.

Assyrian history

MS 2004 Assyria, 1115-1077 BCMS 711 Assyria, 883-859 BCMS 2848 Assyria, 811-783 BCMS 2368 Assyria, 722-705 BC

MS 2180 Assyria, ca. 646 BC

ROYAL ANNALS OF KING TIGLATH-PILESAR I

- CHRONICLE OF SEVERAL MILITARY CAMPAIGNS TO CONQUER NAIRI, LEBANON, AMURRU AND THE HITTITE EMPIRE

- CHRONICLE OF THE FIRST WAR BETWEEN ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA: 'I WENT TO BABYLONIA. FROM THE CITY RIKSU-SHA-ILI WHICH IS ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE LOWER ZAB RIVER AS FAR AS THE CITY LUBDI I CONQUERED. I KNOCKED DOWN THEIR TOWNS AND BURNT THEM WITH FIRE, THEIR POSSESSIONS AND THEIR PROPERTY I CARRIED OFF TO MY CITY ASHUR. I WENT TO THE LAND SUHA - VARIOUS TOWNS WHICH ARE IN THE MIDST OF THE EUPHRATES I CONQUERED. THEIR POSSESSIONS WITHOUT NUMBER I TOOK AWAY. I TORE UP THEIR FIELDS. I CUT DOWN THEIR ORCHARDS'

- CHRONICLE OF THE SECOND WAR BETWEEN ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA: 'AT THE COMMAND OF NINURTA, THE GOD WHO LOVES ME, FOR THE SECOND TIME TO BABYLONIA I WENT. SIPPAR, BABYLON, UPI, THE GREAT SETTLEMENTS OF BABYLONIA I CONQUERED TOGETHER WITH THEIR FORTRESSES. THEIR POSSESSIONS AND THEIR PROPERTY WITHOUT NUMBER I TOOK AWAY. THE PALACES OF BABYLON, THE CITY OF MARDUK-NADIN-AHHI, KING OF BABYLONIA, I KNOCKED DOWN. THE MANY OBJECTS OF HIS VARIOUS PALACES I CARRIED OFF. THE KING OF BABYLONIA, IN THE STRENGTH OF HIS SOLDIERS AND HIS CHARIOTS HE PUT HIS TRUST, AND HE CAME AFTER ME. IN THE CITY SITULA WHICH IS NORTH OF THE CITY AKKAD WHICH IS OPPOSITE THE TIGRIS RIVER, HE ENGAGED IN BATTLE WITH ME. HIS MANY CHARIOTS I DISPERSED, THE DEFEAT OF HIS WARRIORS AND HIS FIGHTERS IN THE MIDST OF THAT BATTLE I BROUGHT ABOUT. HE RETREATED AND RETURNED TO HIS LAND'

- DETAILED ACCOUNT OF THE REBUILDING OF THE GREAT CITY WALL OF PAKUTE AND ITS PRINCIPAL PALACE

MS in Middle Assyrian on clay, Assyria, 1115-1077 BC, 1 tablet, 19,7x14,5x3,3 cm, single column, 35+35 lines in Assyrian cuneiform script, with 60 'fire holes'.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1995, quarter green morocco gilt folding case, by Aquarius.

Context: Another inscription of Tiglath-pileser is MS 2795.

Commentary: The present tablet represents a major new contribution to the history of the world in its detailed account of two hitherto unknown wars between 2 of the 3 greatest powers of the period, Assyria and Babylonia, texts 2 and 3. The campaigns in text 1 are known from other sources, while the city Pakute in text 4 is attested here for the first time.

Exhibited: 'Preservation for access: Originals and copies'. On the occasion of the 1st International Memory of the World Conference, organized by the Norwegian Commission for UNESCO and the National Library of Norway, at the Astrup Fearnley Museum of Modern Art, Oslo, 3 June - 14 July 1996.

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF ASSURNASIRPAL II: CALAH I RESTORED. A TEMPLE OF MY LADY I ESTABLISHED THERE. THIS TEMPLE DEDICATED TO THE GODS AND SUBLIME, WHICH WILL ENDURE FOREVER, I WILL DECORATE SPLENDIDLY. PART OF THE 'STANDARD INSCRIPTION' FROM THE ROYAL PALACE IN CALAH, MENTIONED IN THE BIBLE

MS in Assyrian on basalt stone, Nimrod (Calah), Assyria, 883-859 BC, 1 plaque, 43x26 cm, single column, (43x23 cm), 10 lines in display cuneiform script. Complete standard inscription: ca. 50x225 cm (ca. 45x215), 21 long lines with friezes over and below (both ca. 70x225 cm).

Context: Most of the reliefs and inscriptions are in British Museum and Louvre. Further holdings in New York Historical Society, Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University.

Commentary: From the East Wing of the Palace, room I. The site of the temple is mentioned in Genesis 10:11-12: 'Out of that land went forth Assur, and builded Nineveh, and the city of Rehoboth, and Calah, and Resen between Nineveh and Calah, the same is a great city'. Genesis 10:1-12 mentions that the builder of Calah was Nimrod, son of Cush, son of Ham, son of Noah. The 'standard inscription' is a 22-line text that records Assurnasirpal's victories, his greatness and describes the building of his palace at Calah. The inscription exists in many variants, all of which come from the slabs lining the walls of the palace. The version presented here is recorded by Y. Le Gac: Les incriptions d'Ashur-nasir-pal II, roi d'Assyrie. Paris 1908, p. 187. What makes the present inscription of interest, is that it includes a detailed description of the very palace that it adorned, and that Calah is directly referred to in Genesis 10:11-12.

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF ADAD-NIRARI III: - MY DREAD OVERWHELMED THEM - I CONSTRUCTED A CITY - I WENT UP AND MADE SACRIFICES - PRIME SON OF ASSUR-NASIR-APLI - PRINCES HAS NO RIVAL - SON OF TUKULTI-NINURTA

MS in Neo Babylonian on bronze, Assyria, 811-783 BC, lower part of the garment of a giant statue, 42x26x5-10 cm remaining, single column, 19 lines in a large formal cuneiform script, the lower border of the garment, 6x18 cm, divided into 4 square compartments with decorative designs of Assyrian type.

Commentary: A unique royal inscription. There seems to be no other remains of so large a statue of an Assyrian king surviving. Assur-nasir-apli II was the son of Tukulti-Ninurta II and the great grandfather of Adad-nirari III.

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF SARGON II OF ASSYRIA, DESCRIBING HIS CONQUESTS GENERALLY, MENTIONING: BIT-HABAN, PARSHUMASH, MANNAEA, URARTU; THE HEROIC MAN WHO DEFEATED HUMBANIGASH, KING OF ELAM; WHO MADE THE EXTENSIVE BIT-HUMRIYA (HOUSE OF OMRI) TOTTER, THE DEFEAT OF MUSRU IN RAPIHU; BOUND TO ASHUR, WHO CONQUERED THE TAMUDI; WHO CAUGHT THE IONIANS IN THE SEA LIKE A BIRD-CATCHER; ALSO BIT-BURTASHA, KIAKKI AND AMRISH, THEIR RULERS; WHO DROVE AWAY MIT(MIDAS), KING OF MUSHKU; WHO PLUNDERED HAMATH AND CARCHEMISH; GREAT HAND CONQUERED, THE DEVASTATOR OF URARTU, MUSASIR; THE URARTIANS BY THE TERROR OF HIS WEAPONS, KILLED BY HIS OWN HANDS; WHO DESTROYED THE PEOPLES OF HARHAR, WHO GATHERED THE MANNAEANS, ELLIPI; WHO CHANGED THE ABODE OF PA, LALLUKNU; WHO FLAYED THE SKIN OF ASHUR-L#39;I, THEIR GOVERNOR; WHO IMPOSED THE YOKE OF ASHUR ON SHURD FROM MELIDU, HIS ROYAL CITY; THE FEARSOME ONSLAUGHT, WHO HAD NO FEAR OF BATTLE, -

MS in Neo Babylonian on clay, Nimrod, Assyria, 722-705 BC, 1 partial 8-facetted prism, 6,2x12,0 cm remaining, 8 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: 1 fragment of a cylinder with the same inscription, also in Neo Babylonian, is known.

Commentary: The present MS is related to the clay cylinders from Khorsabad, but they are in Assyrian. These cylinders were written in Nimrud, Assyria, for being sent to Babylonian cities to be deposited in foundation deposits in buildings in Babylonia.

TO NAB EXALTED LORD, WHO DWELLS IN EZIDA, WHICH IS IN NINEVEH, HIS LORD: I ASHURBANIPAL, KING OF ASSYRIA, THE ONE LONGED FOR AND DESTINED BY HIS GREAT DIVINITY, WHO, AT THE ISSUING OF HIS ORDER AND THE GIVING OF HIS SOLEMN DECREE, CUT OFF THE HEAD OF TE'UMMAN, KING OF ELAM, AFTER DEFEATING HIM IN BATTLE, AND WHOSE GREAT COMMAND MY HAND CONQUERED UMMAN-IGASH, TANMARIT, PA'E AND UMMAN-ALTASH, WHO RULED OF ELAM AFTER TE'UMMAN. I YOKED THEM TO MY SEDAN CHAIR, MY ROYAL CONVEYANCE. WITH HIS GREAT HELP I ESTABLISHED DECENT ORDER IN ALL THE LANDS WITHOUT EXCEPTION. AT THAT TIME I ENLARGED THE STRUCTURE OF THE COURT OF THE TEMPLE OF NAB MY LORD, USING MASSIVE LIMESTONE. MAY NABLOOK WITH JOY ON THIS, MAY HE FIND IT ACCEPTABLE. BY THE RELIABLE IMPRESS OF YOUR WEDGES MAY THE ORDER FOR A LIFE OF LONG DAYS COME FORTH FROM YOUR LIPS, MAY MY FEET GROW OLD BY WALKING IN EZIDA IN YOUR DIVINE PRESENCE

MS in Neo Assyrian on limestone, Nineveh, Assyria, ca. 646 BC, 1 limestone slab, 47x42x4 cm, single column, 19 lines in Neo Assyrian cuneiform script.

Commentary: King Ashurbanipal (669-631 BC) rebuilt Ezida, the temple of Nab the god of writing.

Sumerian literature

MS 3396 Sumer, ca. 2600 BCMS 3026 Babylonia, 19th-18th c. BCMS 2652/1 Babylonia, ca. 18th c. BCMS 3283 Babylonia, 1900-1700 BCMS 2367/1 Babylonia, 20th-17th c. BC

INSTRUCTIONS OF SHURUPPAK, proofRB COLLECTION

MS in Sumerian on clay, Sumer, ca. 2600 BC, 1 tablet, 8,7x8,7x2,5 cm, 2 columns + 2 blank columns, 8+8 compartments in cuneiform script, reverse blank. Context: For the Old Babylonian recension of the text, see MSS 2817 (lines 1-22), 3352 (lines 1-38), 2788 (lines 1-45), 2291 (lines 88-94), 2040 (lines 207-216), 3400 (lines 342-345), MS 3176/1, text 3, and 3366.

Context: For the Old Babylonian recension of the text, see MSS 2788 (lines 1-45), 2291 (lines 88-94) and 2040 (lines 207-216).

Commentary: The present Early Dynastic tablet is one of a few that represent the earliest literature in the world. Only 3 groups of texts are known from the dawn of literature: The Shuruppak instructions, The Kesh temple hymn, and various incantations (see MS 4549 ). The instructions are addressed by the ante-diluvian ruler Shuruppak, to his son Ziusudra, who was the Sumerian Noah, cf. MS 3026 , the Sumerian Flood Story, and MS 2950 , Atra- Hasis, the Old Babylonian Flood Story. The Shuruppak instructions can be said to be the Sumerian forerunner of the 10 Commandments and some of the proofrbs of the Bible: Line 50: Do not curse with powerful means (3rd Commandment); lines 28: Do not kill (6th Commandment); line 33-34: Do not laugh with or sit alone in a chamber with a girl that is married (7th Commandment); lines 28-31: Do not steal or commit robbery (8th Commandment); and line 36: Do not spit out lies (9th Commandment).

FLOOD STORY

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 19th-18th c. BC, 1/4 tablet, 6,4x5,5x2,3 cm, ca. 35 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: For 5 of the 6 Sumerian forerunners of the Gilgamesh Epic, see MSS2652/1-2 , 2887, 3026 , 3027 and 3361.

Commentary: Mankind's oldest reference to the Deluge, together with 1/3 tablet in Philadelphia, the only other tablet bearing this story in Sumerian. The tablets share several lines from the beginning of the Flood story, but the present tablet also offers new lines and textual variants. Ziusudra, the Sumerian Noah, is here described as 'the priest of Enki', which is new information.

The Sumerian Flood story is one of the 6 forerunners to the Old Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic, the source for the Old Babylonian myth Atra-Hasis, and for the Biblical account of the Flood (Genesis 6:5-9:29), written down several hundred years later.

According to British Museum, their Neo Babylonian tablet with the Flood story as a part of Gilgamesh, is perhaps the most famous tablet in the world. The present tablet is over 1000 years older.

Exhibited: Tigris 25th anniversary exhibition. The Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo, 30.1. - 15.9.2003.

GILGAMESH AND KING AKKA OF KISH, LINES 1 - 60

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 18th c. BC, 1 tablet, 14,5x5,5 cm, single column, 60 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: In line 25 there is a possible, much earlier parallel from ca. 2600 BC, in MS 1952/37. There would possibly have been a companion tablet with the remaining lines, 61-114 of this work.

For 5 of the 6 Sumerian forerunners of the Gilgamesh Epic, see MSS 2652/1-2 , 2887, 3026 , 3027 and 3361.

Commentary: There are two literary traditions concerning the war between Kish and Uruk, the present and Shulgi Hymn O, taking up themes from other tales, such as Gilgamesh in the Cedar forest, and Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, eventually melting together in the famous Epic of Gilgamesh.

Exhibited: Tigris 25th anniversary exhibition. The Kon-Tiki Museum, Oslo, 30.1. - 15.9.2003.

| 1. |

DEBATE BETWEEN SUMMER (EMESH) AND WINTER (ENTEN) |

| 2. |

CREATION OF THE WORLD, PART OF THE SUMERIAN CREATION STORY |

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 1900-1700 BC, a 4-sided prism, 20x12x11 cm, 2 columns per side, 50 lines per column in cuneiform script.

Context: Other tablets of the Sumerian creation story are MSS 2110 , 2423/1-5 and 3293.

Commentary: The prism had the full text of some 400 lines, but with losses along one corner. This is the most substantial MS of the text. The end is different from the published edition, which has 318 lines. The disputation between Summer and Winter remains unsolved, since their verdict insists that they are complementary and should remain so. There are parallels to the Biblical creation story: 'The Lord lifted his head in pride, bountiful days arrived. Heaven and earth he regulated and the population spread wide' (Genesis 1:31-2:1), with further references to Genesis 1:11-13; 20-25.

- ENHEDU' ANNA: HYMN C TO INANNA 1 - 16: 'INANNA, STOUT-HEARTED, AGGRESSIVE LADY, MOST NOBle OF THE ANUNNA-GODS, - SHE IS A BIG NECK-STOCK CLAMPING DOWN ON THE GODS OF THE LAND, - ONCE SHE HAS SPOKEN, CITIES BECOME RUIN-HEAPS, A HOUSE OF DEVILS'

- proofRB

MS in Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 20th-17th c. BC, 1 tablet, 21x17x4 cm, 3 columns, 16+16+16+4 lines in cuneiform script by a teacher of a scribal school in column 1, with 2 students repeating the hymn in columns 2 and 3.

Context: The same text as on MS 2367/3. Hymns to Inanna are MSS 2367/1, 2367/3, 2647, 2698/1-2, 2784, 3286, 3301, 3376 and 3384. Hymns by Enhedu'Anna are MSS 2367/1-4 ,, 2647, 3376 and 3384.

Commentary: Enheduanna was daughter of King Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BC), founder of the first documented empire in Asia. Enheduanna emerges as a genuine creative talent, a poetess as well as a princess, a priestess and a prophetess. She is, in fact, the first named and non-legendary author in history. As such she has found her way into contemporary anthologies, especially of women's literature.

Babylonian literature

MS 2866 Babylonia, 18th c. BCMS 3025 Babylonia, 19th-18th c. BCMS 4573/1 Babylonia, 2000-1600 BCMS 2950 Babylonia, 1900-1700 BCMS 5108 Babylonia, 1900-1700 BCMS 2624 Babylonia, 1700-1500 BC

MY BELOVED KNOWS MY HEART,

MY BELOVED IS SWEET AS HONEY,

SHE IS AS FRAGRANT TO THE NOSE AS WINE,

THE FRUIT OF MY FEELINGS -, POEM

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 18th c. BC, 1 tablet, 11,0x5,7 cm, 23 lines in cuneiform script.

Commentary: So far a unique love poem, without parallels for this early period.

GILGAMESH EPIC:: THE DREAM OF GILGAMESH, INCLUDING THE FIRST TWO OF GILGAMESH'S NIGHTMARES FROM THE EXPEDITION TO THE CEDAR FOREST AND ENKIDU'S EXPLANATIONS OF THEM

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 19th-18th c. BC, 1 tablet, 20,3x7,5x3,2 cm, 85 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: For 5 of the 6 Sumerian forerunners of the Gilgamesh Epic, see MSS 2652/1 -2, 4, 2887, 3026 , 3027 and 3361.

Commentary: Gilgamesh, the oldest substantial world literature, is mostly preserved on a set of 12 Neo Babylonian tablets, which however, are about 1000 years later than the present Old Babylonian original version. Only one more large intact tablet and 9 fragments of this version are known. One of the fragments is MS 2652/5. None of these are overlapping the present text, which makes this tablet the sole witness to this part of the Old Babylonian Gilgamesh. Less than half of the text has parallels with the later Middle Babylonian version from Hathusa, and the Neo Babylonian Gilgamesh tablet IV. Only about 2/3 of the epic is preserved. The present tablet adds 55 new lines to it, including an entirely new dream and its explanation.

Published: A.R. George: The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic. Introduction, critical edition and cuneiform texts. Oxford, University press, 2003. 2 vols. Also to be published in the series Manuscripts in The Schen Collection, ed. Jens Braarvig.

HUMBABA'S HEAD WITH WRINKLES, A BROAD GRIN AND STRAIGHT HAIR, VOTIVE CLAY CAST

MS on clay, Babylonia, 2000-1600 BC, 1 circular votive head, 7,3x7,1x3,0 cm, uninscribed.

Context: MSS 4573/1-3 come from a hoard of 4 casting forms and 56 casts of an artist's workshop, not yet distributed for votive use in private homes.

Commentary: Humbaba belongs in the tale of Gilgamesh in the Cedar Forest, where Gilgamesh and Enkindu kill the demi god, Humbaba. 'Humbaba, his voice is the Deluge, his speech is Fire, and his breath is Death!' See MS 3025.

ATRA-HASIS, EPIC, THE END OF THE BABYLONIAN FLOOD STORY: - IN HIS HEART HE DID NOT TAKE COUNSEL(?) -, THE ANIMALS HAD SWELLED UP -, MANKIND HAD SWELLED UP -, AT THAT TIME THE SAGE WATRAM-HASIS SAW THIS. HE SPOKE TO EA HIS LORD, (ENLIL WAS DISTURBED BY) THE NOISE OF (THE PEOPLE)

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 1900-1700 BC, upper half of a tablet, 6,5x5,2x2,5 cm, single column, 12 lines of originally 40 lines in cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 2000, blue quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: The present part of Atra-Hasis is so far missing on all known tablets. It could belong to BM tablet I, lines 360-365, with a gap concerning the plague prior to the Flood, or to BM tablet III, column 3 after line 27, and column 4 before line 30, where 54 lines are missing, covering the flood story from its peak to the period after the flood had dried up. The primary cause of swelling is development of interior gasses following floods and drowning or famine. According to W.G. Lambert and A.R. Milland: Atra-Hasis: The Babylonian story of the flood. Eisenbrauns 1999, pp. 31-41. There are only some 13 tablets and fragments preserved of the Atra-Hasis Epic, in at least 4 different recentions. Very much of the epic is lost. Another part of the Atra-Hasis epic is MS 5108.

Commentary: The Old Babylonian Flood story told in both the epics of Atra-Hasis and Gilgamesh was written about 200 years before the account in the Bible, Genesis 6:5-8:22. While the cause of the Flood in the Bible was mankind's wickedness and violence, the Old Babylonian cause was the noisy activities of humans, preventing the chief god, Enlil, from sleeping, actually mentioned in the present tablet.

The harsh account of swollen animals and human bodies was apparently deleted from the Biblical Flood story, even if it would have been the first sight meeting Noah leaving the Arc.

ATRA-HASIS EPIC, TABLET 2, COLUMN 4:11 - 20; COLUMN 8:34 - END; AND CA. 40 NEW LINES: - THEY BROKE THE COSMIC BARRIER! - THE FLOOD WHICH YOU MENTIONED, WHOSE IS IT? - THE GODS COMMANDED TOTAL DESTRUCTION! ENLIL DID AN EVIL DEED ON THE PEOPLE! THEY COMMANDED IN THE ASSEMBLY OF THE GODS, BRINGING A FLOOD FOR A LATER DAY, 'LET US DO THE DEED!' ATRA-HASIS -

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 1900-1700 BC, upper half of a tablet, 13,0x12,3x4,2 cm, 2+2 columns, 15+17+20+24+1 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: There are only some 13 tablets and fragments preserved of the Atra-Hasis Epic, in at least 4 different recentions. Very much of the epic is lost. The ca. 40 new lines on the present tablet improofs this situation. Another part of the Atra-Hasis epic is MS 2950.

Commentary: The Old Babylonian Flood story told in both the epics of Atra-Hasis and Gilgamesh was written about 200 years before the account in the Bible, Genesis 6:5-8:22. While the cause of the Flood in the Bible was mankind's wickedness and violence, the Old Babylonian cause was the noisy activities of humans, preventing the chief god, Enlil, from sleeping. When the Neo Babylonian account of the Flood story as part of the Gilgamesh epic was discovered in the 19th c., it caused a sensation. It turned out that this was a abbreviated account extracted from the Old Babylonian Atra-hasis epic, written about 1000 years earlier. The Flood is the climax of the whole story. The gods created the human race to take over the hard agricultural work in the universe. They were created with the power to reproduce, but without the fate of dying as an result of age. The human race multiplied and made such noise that the chief Sumerian god, Enlil, could not sleep. Accordingly he tried to reduce their numbers, first by plague, then by famine. In each case the god Ea, who was mainly responsible for creating the human race, frustrated the plan. Enlil then got all the gods to swear to co-operate in exterminating the whole human race by a huge flood, which failed because Ea got his favourite , Ziuzudra (the Old Babylonian Noah), to build an ark and so save the human race and the animals. This tablet starts when the second attempt, famine, had just failed, Enlil was looking into what had happened and making another plan.

LITERARY AND RELIGIOUS SPEECH, STARTING: LIKE A CITY WITH SUPREME POWER MY CITY IS URUK, THE CITY OF THE KING. BUT YOU, WHO GREW UP IN MY CITY AND MY LAND, HAVE PLUNDERED THE TEMPLE OF MY LORD, HAVE DESPOILED THE PROPERTY OF MY LADY. -

MAY THE FORMER DAYS OF CONFLICT PASS ON, AND MAY THE NOW DISTANT DAYS OF PEACE BE ESTABLISHED. - CONFER AND ANSWER THAT HE MAY BE SET FREE, BECAUSE TO ME YOU ARE A FOOL. -

MS in Neo Sumerian and Old Babylonian on clay, Uruk, Babylonia, 1700-1500 BC, 1 tablet, 20,0x6,4x2,2 cm, 63 double lines in a minute expert cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1998, blue quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Commentary: The text is bilingual, first line in artificial Sumerian, quite unlike the real Sumerian of the 3rd millennium, immediately followed by a line with the Old Babylonian translation. The text is hitherto unknown.

Sumerian Block printing in blind on clay

ROYAL INSCRIPTION OF NARAM-S: NARAM-S WHO BUILT THE TEMPLE OF INANNA

MS in Sumerian on clay, Akkad, Sumer, 2291-2254 BC, 1 brick printing block, 13x13x10 cm, 3 lines in a large formal cuneiform script, large loop handle.

Context: There are only 2 more brick stamps of Naram-S known, one intact with a cylindrical handle, and a tiny fragment in British Museum.

Commentary: Naram-S was the first king to use blocks for printing bricks. Prior to him the inscriptions on the bricks were written by hand. These 3 brick stamps known, are the earliest evidence of printing, in this case blindprinting on soft clay.

TO NINGIRSU, MIGHTY WARRIOR OF ENLIL, GUDEA RULER OF LAGASH MADE IT SPLENDID FOR HIM AND BUILT FOR HIM THE TEMPLE OF THE SHINING IMDUGUD BIRD AND RESTORED IT

Blockprint in blind in Sumerian on clay, Lagash, Sumer, 2141-2122 BC, 1 brick, 32x32x7 cm, 6+4 columns, in cuneiform script.

Context: Foundation inscriptions of Gudea in The Schen collection are MSS 1877, 1895, 1936, 1937 and 2890. Building cones, see MSS 1791/1-2.

Commentary: Gudea built or rather rebuilt, at least 15 temples in the city-state of Lagash. The present brick has deposits of the bitumen that originally bound the bricks together in the wall of the temple.

AMAR-SIN OF NIPPUR, CHOSEN BY ENLIL, MIGHTY HERO, THE TEMPLE OF ENLIL, BRICK STAMP INSCRIPTION

MS in Neo Sumerian on white marble, Sumer, 2046-2038 BC, 1 brick printing block, 18,5x10,0x3,5 cm, single column, 7 lines in cuneiform script, with a handle on the back.

Context: Bricks of King Amar-Sin with full texts are MSS 1878 and 1914.

Commentary: Brick printing blocks are so rare as objects that there is a theory that they were broken when a production run was finished. Those that are known are almost never intact. There are some broken ones from the Old Acadian Period, including the intact MS 5106, but they are of terracotta. Until this one there were no examples of an UR III brick printing block known at all, and the material of their construction was a complete mystery.

The inscription is a well known one, but the last 3 lines have not been cut, apart from the first sign in line 7. This printing block was never used, but discarded by the scribe due to a slight chipping to the inscription. Since the natural medium for writing at this time, was clay, the process of impressing a block into wet soft clay can be seen as the first known example of true printing. Some of the printing blocks even had 'movable type' so that the inscription relating to more than one building could be accommodated with a minimum of effort.

Exhibited: TEFAF Maastricht International Fine Art and Antiques Fair, 12-21 March 1999.

AMAR-SIN IN NIPPUR, CALLED BY ENLIL WHO SUPPORTS THE TEMPLE OF ENLIL, POWERFUL MALE, KING OF UR, KING OF THE 4 QUARTERS OF THE WORLD

Blockprint in blind in Neo Sumerian on clay, Nippur, Sumer, reign of King Amar-Sin, 2047-2038 BC, 1 brick, 17x19x6 cm, originally ca. 33x33x6 cm, 9 columns, (10x11 cm) in cuneiform script.

Context: A original brick printing block of Amar-Sin is MS 2764.

Commentary: Enlil was the chief Sumerian god, whose main temple was in Nippur.

See also MS 1876/1 , Hammurabi brick, Babylonia, 1792-1750 BC

Sumerian music

LEXICAL LIST OF 9 TYPES OF MUSICAL STRINGS, 23 TYPES OF MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS AND MUSIC, INCLUDING DIFFERENT TYPES OF STRINGED INSTRUMENTS SUCH AS HARP AND LYRE, AS WELL AS HITHERTO UNKNOWN INSTRUMENTS; FURTHER LAPIS LAZULI, BEDS, COPPER UTENSILS, TEXTILES, DOMESTIC ANIMALS AND SINEWS, JEWELLERY, WEAPONS, LEATHER PARTS OF YOKE, STRAPS, SACKS, TYPES OF SHEEP, KNIVES, AROMATICS AND PERFUMES, REED OBJECTS, GRAINS AND FLOURS, ETC.

MS in Sumerian on clay, Sumer, 26th c. BC, upper half of a huge tablet + fragment of lower part, 20x30x5 cm + 9x18x5 cm, originally ca. 40x30x5 cm, 16+9 and 7+7 columns, 437+ ca. 100 lines remaining in cuneiform script, circular depressions introducing each new entry.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1996, green quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: Similar, smaller tablets are known from Fara or Tell Abu Salabikh. 3 compilations all from 26th c. BC have music instruments. The present tablet is almost a duplicate of a relatively well-known lexical list, discussed by Miguel Civil in Cagni, Ebla 1975-1985, pp. 133 ff. The obverse is an abbreviated recension with minor changes in the sequence of the entries. The reverse is the continuation of the unfinished Fara recension.

Commentary: The earliest known record of music and musical instruments in history. The name of one of the stringed instruments is a Semitic word, ki-na-ru, the later kinnaru known from the Mari letters and Ras Shamra texts (13th c. BC, cfr. MS 1955/1-6 ), and the still later Biblical Hebrew kinnor. The system of phonetic notation in Sumer and Babylonia is based on a music terminology that gives individual names to 9 musical strings or 'notes', and to 14 basic terms describing intervals of the 4th and 5th that were used in tuning string instruments (according to 7 heptatonic diatonic scales), and terms for 3rds and 6ths that appear to have been used to fine tune (or temper in some way) the 7 notes generated for each scale. The combination of string names and interval terms is used to describe the tuning procedure and the generation of the 7 scales and form a skeletal phonetic notation. (The New Grove, 2nd ed., vol. 18, p. 74.) The oldest musical instruments known are a ca. 41 000 BC flute made of bear bone, found in 1995 at a Neanderthal site in Slovenia, and 6 intact and 30 fragmentary crane bone flutes from Jiahu, in the Chinese province of Henan, dated to 9000-7700 BC. One crane bone flute is still in playing order, the earliest instrument possible to play.

HEBE-ERIDU THE SON OF ADAD-LAMASI SAT WITH IL-SIRI IN ORDER TO LEARN MUSIC. AT THAT TIME, IN ORDER TO STUDY SINGING, THE TIGIDLU-INSTRUMENT, THE ASILA, TIGI INSTRUMENT, AND THE ADAB INSTRUMENT SEVEN TIMES, ADAD-LAMASI PAID IL-SIRI 5 SHEKELS OF SILVER. ILI-IPPALSANI, THE SCHOOLMASTER

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 1900-1700 BC, 1 tablet, 6,5x4,4x2,0 cm, single column, 13 lines in cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 2000, blue cloth gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: Cf. MS 2340 listing 23 types of musical instruments.

Commentary: There are texts of dialogues between a teacher and a scribe, (Schooldays, see MS 4481 ) and between an examiner and a student, but a text concerning music lessons is so far unique.

Old Babylonian cuneiform musical notation

MS 5105

MS 5105

MUSICAL NOTATION OF 2 ASCENDING CONSECUTIVE HEPTATONIC SCALES TO BE PLAYED ON A 4 STRINGED LUTE TUNED IN ASCENDING FIFTHS: C - G - D - A, USING FRETS; SCHOOL TEXT

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 2000-1700 BC, 1 lenticular tablet, diam. 9,0x3,2 cm, 2 double columns, each of 7 ruled lines with numbers in Old Babylonian cuneiform notation, with headings, 'intonation' and 'incantation', respectively.

Context: The only other complete music text is a later Hurrian hymn written in the mode of nidqibli, which is the enneatonic descending scale of E.

Commentary: The oldest musical notation known so far. Lutes are not preserved from the Old Babylonian period. The earliest known description of a lute dates from the middle of the 10th c., of a 9th c. instrument, Oxford, Bodleian library MS Marsh 521. The present notation system gives contemporary information on the Old Babylonian 4 stringed lute. It further attests that frets were used, and that their values, tonal and semitonal, were purposely calculated. Most significantly the discovery of this text attests of a music syllabus in educational institutions about 4000 years ago.

Published: To be published by Richard Dunnbrill: An Old Babylonian music text, from where the information has been taken.

Sumerian law

THE UR-NAMMU LAW CODE

CODE OF 57 LAWS INCLUDING CRIMINAL LAW, FAMILY LAW, INHERITANCE

LAW, LABOUR LAW INCLUDING SLAVE RIGHTS, AND AGRICULTURAL AND COMMERCIAL TARIFFS

MS in Sumerian on clay, Sumer, reign of King Shulgi, 2095-2047 BC, 1 cylinder, l. 28 cm, diam. 12 cm, 8 columns (originally 10 columns), 243 lines in cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1996, green quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: For the Hammurabi law code, see MS 2813 .

Commentary: The Ur-Nammu law code is the oldest known, written about 300 years before Hammurabi's law code. When first found in 1901, the laws of Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC) were heralded as the earliest known laws. Now older collections are known: The laws of the town Eshnunna (ca. 1800 BC), the laws of King Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (ca. 1930 BC), and Old Babylonian copies (ca. 1900-1700 BC) of the Ur-Nammu law code , with 26 laws of the 57 on the present MS. This cylinder is the first copy found that originally had the whole text of the code, and it is the world's oldest law code MS. Further it actually mentions the name of Ur-Nammu for the first time.

Hammurabi's laws represented the inhuman Law of Retaliation, 'an Eye for an Eye'. One would expect the 300 years older laws of Ur-Nammu would be even more brutal, but the opposite is the case: 'If a man knocks out the eye of another man, he shall weigh out 1/2 a mina of silver'.

Babylonian law

THE HAMMURABI LAW CODE

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 1750 BC, 1 tablet, 11,7x10,0x3,0 cm (originally ca. 13x10x3 cm), 2 columns, 48 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: The complete text is 282 laws of which 247 are on the famous black basalt stele in Louvre. Cf. MS 2064 , The Ur- Nammu law code, the oldest laws known.

Commentary: Hammurabi (1792-1750 BC), the great king who created the Old Babylonian empire, is today mostly remembered for his famous law code. Towards the end of his reign, Hammurabi ordered his law code to be carved on stelae which were placed in the temples bearing witness that the king had performed his important function of 'king of justice' satisfactorily. The stele now in the Louvre, was originally erected in the Sippar temple, but was found in Susa in 1901.

The Hammurabi law code has until recently been considered the oldest, until the laws of Eshnunna (ca. 1800 BC), Lipit-Ishtar (ca. 1930 BC) and Old Babylonian school extracts (ca. 1900-1700 BC) of Ur-Nammu were discovered. Hammurabi's laws represented the inhuman Law of Retaliation, 'an Eye for an Eye', that was taken up in the laws of Moses and subsequent legislation.

Pre-literate counting and accounting

NEOLITHIC PLAIN COUNTING TOKENS POSSIBLY REPRESENTING 1 MEASURE OF GRAIN, 1 ANIMAL AND 1 MAN OR 1 DAY'S LABOUR, RESPECTIVELY

Counting tokens in clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 8000-3500 BC, 3 spheres: diam. 1,6, 1,7 and 1,9 cm , (D.S.-B 2:1); 3 discs: diam. 1,0x0,4 cm, 1,1x0,4 cm and 1,0x0,5 cm (D.S.-B 3:1); 2 tetrahedrons: sides 1,4 cm and 1,7 cm (D.S.-B 5:1).

Commentary: About 8000 BC the Palaeolithic notched tallies representing the simplest form of counting, in one-to-one correspondence, were superseded by Neolithic tokens of various geometric forms suited for concrete counting, including the type of commodity. This invention was used without any discontinuity for 5000 years, prior to the use of abstract numbers which lead to writing about 3300 BC, and then to mathematics ca. 2600 BC. When tokens were invented they were the first clay objects of the Near East, and they first exploited systematically most of the basic geometric forms, such as spheres, tetrahedrons, cones, cylinders, discs, quadrangles, triangles, etc. They were first kept in baskets, leather poaches, clay bowls, etc., and later within clay bullas, see MSS 4631, 4632and 4638.

Exhibited: The Norwegian Intitute of Palaeography and Historical Philology (PHI), Oslo, 13.10.2003-

COMPLEX COUNTING TOKEN REPRESENTING 1 JAR OF OIL

Counting token in stone, Ur?, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 4000-3200 BC, 1 ovoid token, diam. 2,0x2,3 cm, circular line at the top and piercing at the bottom.

Context: For a drum shaped token with zigzag band, see MS 4522/2 (Schmandt-Besserat 3:72), and for disk type tokens, see MSS 4522/3-8.

Commentary: Same type as Schmandt-Besserat 6:14, but pierced at the bottom. The complex tokens were a natural development from the plain tokens (see MSS 5067/1-8) with new forms, added lines, dots and various designs to cover the more advanced accounting needs. They were first kept in baskets, leather poaches, bowls, etc., and then to some extent within bulla-envelopes (see MS 4631), but mainly attached to strings fastened to a bulla (see MS 4523). They lasted until ca. 3200 BC, when they were superseded by counting tablets and pictographic tablets. Some of the earliest tablets have actual tokens impressed into the clay to form numbers and pictographs, and many of the pictographs were illustrations of tokens. An account of 14 jars of oil would just be 14 tokens of the present type. On a pictographic tablet this representation would be substituted by the number 14 and the pictograph of a jar with lid looking similar to the token. This was the first break-through of the invention of writing. For such a pictographic tablet, see MS 4551 . (All 8 tokens MSS 4522/1-8 are illustrated here, text: Counting tokens representing a Jar of oil and various textiles, Near East, ca. 4000-3200 BC.)

BULLA-ENVELOPE WITH 11 PLAIN AND COMPLEX TOKENS INSIDE, REPRESENTING AN ACCOUNT OR AGREEMENT, TENTATIVELY OF WAGES FOR 4 DAYS' WORK, 4 MEASURES OF METAL, 1 LARGE MEASURE OF BARLEY AND 2 SMALL MEASURES OF SOME OTHER COMMODITY

Bulla in clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3700-3200 BC, 1 spherical bulla-envelope (complete), diam. ca. 6,5 cm, cylinder seal impressions of a row of men walking left; and of a predator attacking a deer, inside a complete set of plain and complex tokens: 4 tetrahedrons 0,9x1,0 cm (D.S.-B.5:1), 4 triangles with 2 incised lines 2,0x0,9 (D.S.-B.(:14), 1 sphere diam. 1,7 cm (D.S.-B.2:2), 1 cylinder with 1 grove 2,0x0,3 cm (D.S.-B.4:13), 1 bent paraboloid 1,3xdiam. 0,5 cm (D.S.-B.8:14).

Context: MSS 4631-4646 and 5114-5127are from the same archive. Total number of bulla-envelopes worldwide is ca. 165 intact and 70 fragmentary.

Commentary: While counting for stocktaking purposes started ca. 8000 BC using plain tokens of the type also represented here, more complex accounting and recording of agreements started about 3700 BC using 2 systems: a) a string of complex tokens with the ends locked into a massive rollsealed clay bulla (see MS 4523), and b) the present system with the tokens enclosed inside a hollow bulla-shaped rollsealed envelope, sometimes with marks on the outside representing the hidden contents. The bulla-envelope had to be broken to check the contents hence the very few surviving intact bulla- envelopes. This complicated system was superseded around 3500-3200 BC by counting tablets giving birth to the actual recording in writing, of various number systems (see MSS 3007 and 4647), and around 3300-3200 BC the beginning of pictographic writing (see MSS 2963 and 4551 ).

Exhibited: The Norwegian Intitute of Palaeography and Historical Philology (PHI), Oslo, 13.10.2003-

BULLA-ENVELOPE WITH 17 PLAIN TOKENS INSIDE, REPRESENTING AN ACCOUNT OR WAGES OF TENTATIVELY 1 LARGE MEASURE OF BARLEY, 8 SMALL MEASURES OF BARLEY, 5 MEDIUM AND 3 SMALL MEASURES OF SOME OTHER COMMODITY

Bulla in clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3700-3200 BC, 1 spherical bulla-envelope (complete), diam. ca. 7 cm, cylinder seal impressions of a row of men each carrying a sack on his head towards a large cauldron placed on a rounded stand; and of a line of tall ringstaffs and men; a 3rd impression of a large disk type token or the bottom of a large cone, diam. 2,2 cm, possibly representing the total sum of the complete set of plain tokens inside: 1 sphere diam. 1,5 cm (D.S.-B.2:2), 8 small spheres diam. 0,8 cm of which 1 still sticks to the inside of the bulla (D.S.-B.2:1), 5 cones diam.1,0x1,5 cm (D.S.-B.1:1), 3 small cylinders diam. 0,4xca.1,2 cm (D.S.-B.4:1).

Context: MSS 4631-4646 and 5144-5127 are from the same archive. Only 25 more bulla-envelopes are known from Sumer, all excavated in Uruk. Total number of bulla-envelopes worldwide is ca. 165 intact and 70 fragmentary.

Commentary: 17 tokens is the largest number found inside a bulla-envelope. While counting for stocktaking purposes started ca. 8000 BC using plain tokens of the type here, more complex accounting and recording of agreements started about 3700 BC using 2 systems: a) a string of complex tokens with the ends locked into a massive rollsealed clay bulla (see MS 4523), and b) the present system with the tokens enclosed inside a hollow bulla-shaped rollsealed envelope, sometimes with marks on the outside representing the hidden contents. The bulla-envelope had to be broken to check the contents hence the very few surviving intact bulla- envelopes. This complicated system was superseded around 3500-3200 BC by counting tablets giving birth to the actual recording in writing, of various number systems (see MSS 3007 and 4647), and around 3300-3200 BC the beginning of pictographic writing (see MSS 2963 and 4551 ).

BULLA-ENVELOPE WITH 1 PLAIN TOKEN INSIDE, REPRESENTING AN ACCOUNT OR AGREEMENT OF TENTATIVELY 1 VERY LARGE MEASURE OF BARLEY

Bulla in clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3700-3200 BC, 1 spherical bulla-envelope (complete), diam. 6,0-6,8 cm, cylinder seal impression of several men facing tall ringstaff; and another with animals; token inside: 1 large sphere diam. 2 cm (D.S.-B.2:2). Context: MSS 4631-4646 and 5144-5127 are from the same archive. Only 25 more bulla-envelopes are known from Sumer, all excavated in Uruk. Total number of bulla-envelopes worldwide is ca. 165 intact and 70 fragmentary.

Commentary: While counting for stocktaking purposes started ca. 8000 BC using plain tokens of the type here, more complex accounting and recording of agreements started about 3700 BC using 2 systems: a) a string of complex tokens with the ends locked into a massive rollsealed clay bulla (see MS 4523), and b) the present system with the tokens enclosed inside a hollow bulla-shaped rollsealed envelope, sometimes with marks on the outside representing the hidden contents. The bulla-envelope had to be broken to check the contents hence the very few surviving intact bulla- envelopes. This complicated system was superseded around 3500-3200 BC by counting tablets giving birth to the actual recording in writing, of the sexagesimal counting system (see MSS 3007 and 4647), and around 3300-3200 BC the beginning of pictographic writing (see MSS 2963 and 4551 ).

BULLA FOR HOLDING A STRING OF COMPLEX COUNTING TOKENS CONCERNING A TRANSACTION

Bulla in clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3500-3200 BC, 1 oblong bulla, diam. 2,5x6,5 cm, rollsealed with a line of animals walking left or 2 men standing with arms raised, pierced for holding a string of counting tokens.

Context: For another bulla of the same type, see MS 5113.

Commentary: The bulla originally locked the ends of a string with a number of complex counting tokens attached to it, representing 1 transaction. The string with the tokens was hanging outside the bulla like a necklace. If the string had, say, 5 disk type tokens representing types of textiles, this number could not be tampered with without breaking the seal. The tokens could also be entirely enclosed in the centre of the bulla, see MSS 4631, 4632 and 4638. Tokens were used for accounting purposes in the Near East from the Neolithic period ca. 8000 BC until ca. 3200 BC, when they were superseded by counting tablets and pictographic tablets. Some of the earliest tablets have actual tokens impressed into the clay to form numbers and pictographs, and some of the pictographs were illustrations of tokens, see MS 4551 .

NUMBERS 10 AND 5 +4 + 4 + 4 + 5 + 3

MS on clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3500-3200 BC, 1 elliptical tablet, 6,7x4,4x1,9 cm, 2+1 compartments, 2 of which with 3 columns of single numbers as small circular depressions.

Commentary:Numerical or counting tablets with their more complex combination of decimal and sexagesimal numbers are a further step from the tallies with the simplest form of counting in one-to-one correspondence. They were used parallel with the bulla-envelopes with tokens. The commodity counted was not indicated in the beginning, but was gradually imbedded in the numbers system or with a seal or a pictograph of the commodity added, i. e. development into ideonumerographical tablets, the forerunners to pictographic tablets. There are only about 260 numerical tablets known. Most of them are found in Iran.

NUMBERS 3+4, POSSIBLY REPRESENTING 3 MEASURES OF BARLEY AND 4 MEASURES OF SOME OTHER COMMODITY, IN SEXAGESIMAL NOTATION

MS on clay, Syria/Sumer/Highland Iran, ca. 3500-3200 BC, 1 tablet, 4,4x5,0x2,3 cm, 2 lines with 3 small circular depressions and 4 short wedges.

Numerical or counting tablets with their more complex combination of decimal and sexagesimal numbers are a further step from the tallies with the simplest form of counting in one-to-one correspondence. They were used parallel with the bulla-envelopes with tokens. The commodity counted was not indicated in the beginning, but was gradually imbedded in the numbers system or with a seal or a pictograph of the commodity added, i. e. development into ideonumerographical tablets, the forerunners to pictographic tablets. There are only about 260 numerical tablets known. Most of them are found in Iran.

Exhibited: The Norwegian Intitute of Palaeography and Historical Philology (PHI), Oslo, 13.10.2003-

Arithmetic's

1, MULTIPLICATION TABLE FOR LENGTH MEASURES, WITH THE PRODUCTS EXPRESSED AS AREA MEASURES, THE LENGTH NUMBERS (5, 10, 20, ETC.) IN COLUMN 1 ARE MULTIPLIED WITH THE LENGTH NUMBERS (5X60, 10X60, 20X60, ETC.) IN COLUMN 2 TO GIVE THE COMPLICATED AREA NUMBERS IN COLUMN 3

2. SUCCESSIVE MULTIPLICATION OF SEXAGESIMAL NUMBERS BY 2, FROM 11.5=675 (OR 3/16) IN LINE 2 TO 3.00.00 (=3X60X60=10800) IN LINE 6

MS in Old Sumerian on clay, Sumer, 27th c. BC, 1 tablet, 7,2x7,1x2,0 cm, 28 compartments in cuneiform script.

Commentary: The oldest known mathematical text. Only one nearly as old mathematical table text is known, a table of squares of length measures, with the products expressed as area measures, Berlin VAT 12593. There is a big difference between this kind of multiplication table with explicit lengths and areas and the 1000 years younger Old Babylonian multiplication tables with abstract sexagesimal numbers.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

SUM OF A GEOMETRIC PROGRESSION COMPUTED FROM THE BOTTOM UP. THE FIRST TERM IS 2, THE SECOND TERM IS 2X(1+1/6) = 2 1/3, WRITTEN AS 2;20. THE SUM IS GIVEN IN LINE 1, IN SEXAGESIMAL PLACE VALUE NOTATION; SCHOOL TEXT REPRESENTING AN INHERITANCE PROBLEM FOR 7 BROTHERS

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 20th c. BC, 1 round tablet, 11,0x3,5 cm, 9 lines in cuneiform script. Binding: tasut

Context: No other Old Babylonian mathematical text is written from the bottom up in this way.

Commentary: According to the subscript, the number in each line should be equal to the number in the line above it, minus a seventh of that number. Actually, the 7 numbers in lines 2-8 have been computed from the bottom up, beginning with 2 and then making the number in each line equal to the number in the line below it plus a sixth of that number. The sum of the 7 numbers is recorded in line 1. A numerical error in line 3 is propagated upwards, to lines 2 and 1. The recorded numbers look like very large integers, but are actually all a small integer plus a sexagesimal fraction. The youngest of the 7 brothers gets 2, the next gets 2x(1+1/6), the next 2.20x(1+1/6), etc., or read from the top each brother gets 1/7 less than the brother before him. The tablet certainly has been re-used, and there are traces of possible numerical notation from its previous use.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

MULTIPLICATION TABLE FOR 1.12(=72), IN THE SUMERIAN SEXAGESIMAL SYSTEM

MS on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 7,8x4,7x1,8 cm, single column, 15+8 lines in cuneiform script.

Commentary: The number 72 or 1 1/5 is the sexagesimal reciprocal of 50, which appears in the standard tables of reciprocals. Scholars have used the absence of any multiplication tables of 1 1/5 as evidence that they did not exist, and that Babylonians did not have multiplication tables for all sexagesimal numbers appearing in their standard table of reciprocals. The present unique tablet proofs that making such assumptions is groundless.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

EXTREMELY LARGE 15-PLACE SEXAGESIMAL NUMBER 13 22 50 54 59 09 29 58 26 43 17 31 51 06 40, EQUALLING THE 20TH POWER OF 20, WHICH IS 104,857,600,000,000,000,000,000

MS on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 4,5x11,7x2,8 cm, single column, 2 lines in cuneiform script.

Commentary: The number 104 quintillions, 857 quadrillions and 600 trillions is so large that it occupies 2 lines on the obverse and continues on the reverse, being one of the largest numbers recorded on a cuneiform tablet.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

MS 2221

MATHEMATICAL CALCULATIONS ON CARRYING BRICKS AND MUD, THE 4X4 TABLE LISTS CONSTANTS FOR CARRYING THE 3 MOST COMMON BRICK SIZES AND MUD, THE LOAD OF 6 BRICKS, 50 MINAS (25 KG), THAT ONE WORKER CAN CARRY, AND THE DAILY CARRYING DISTANCE, 45.60 LENGTH UNITS = CA. 10,8 KM

MS on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 5,0x5,2x2,3 cm, 3 + 4 columns, 9+6 lines in cuneiform script.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

Algebra

TABLE WITH DATA FOR SOLVING CUBIC EQUATIONS, IN THE SUMERIAN SEXAGESIMAL SYSTEM

MS on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 7,6x4,4x2,3 cm, 3 columns, 30 lines in cuneiform script.

Context: The only similar text known before is a Late Babylonian table text, where the numbers m at left take the values nxnx(n+1). Problems of the mentioned type are known from a large Old Babylonian clay tablet (BM 85200+VAT 6599).

Commentary: Every line of the table says, 'm has the root n'. The numbers n at right take the values 1 to 30. The numbers m at left take the corresponding values nx(n+1)x(n+2). In the 6th line, for instance, n = 6 and m = 6x7x8 = 336 = 5x60 + 36. The table was probably used to set up a series of problems leading to cubic equations guaranteed to have integers as solutions. The problems would have been of the form 'An excavated room. Its length equals its width plus 1 cubit. Its height equals its length. Its volume plus its bottom area is ... (a given number).'

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

THREE NUMBERS ARE RECORDED: 1 1 1 1 (60 CUBED + 60 SQUARED + 60 + 1), AND 13 AND 4 41 37

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 2,9x2,9x1,4 cm, single column, 2 lines in cuneiform script.

Commentary: The meaning of the text is that the first number, 1 01 01 01 in sexagesimal place value notation, is exactly divisible by 13, and that the quotient is 4 41 37. A dressed up version is known from an early Old Babylonian tablet from Ur, where 1 01 01 01 sheep are divided between 13 shepherds.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

MS 5112

MS 5112

| 1. |

EQUATIONS FOR THE SIDES OF ONE, TWO, OR MORE SQUARES |

| 2. |

EQUATIONS FOR THE SIDES OF A RECTANGLE |

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, probably later than 1700, upper half of a tablet, 8,9x9,8x2,7 cm, 2+2 columns, 125 lines in a clear minute cuneiform script.

Commentary: A collection of 16, originally 23, mathematical problem texts. The problem texts were the higher mathematics of the time, and for the better students only. The tablet is probably post-Old Babylonian.

Geometry

EIGHT MATHEMATICAL PROBLEMS WITH DRAWINGS OF SUBDIVIDED TRAPEZOIDS AND TRIANGLES

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, 21,0x8,2x2,9 cm, 92 lines in cuneiform script, drawings to each problem.

Commentary: Problems about trapezoids or triangles divided into two or more smaller parts by transversals parallel to the base were popular in Old Babylonian mathematics. Such problems led to systems of linear or quadratic equations. One particular type of problems for divided trapezoids led to the equation square a + square b = 2 square c. Old Babylonian mathematicians could find solutions in integers to both this equation and the similar equation square a + square b = square c, at least 1200 years before Pythagoras.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

MS 3049

MS 3049

PROPERTIES OF CHORDS OF CIRCLES, HERE CALLED BOW STRINGS, AND DIAMETERS IN CIRCLES

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 17th c. BC, upper left quarter of a tablet, 11,5x6,4x2,2 cm, single column, 43 lines in an expert cuneiform script, signed by the scribe, drawings of 2 circles with diameters and chords indicated.

Commentary: This is a high quality tablet possibly from a royal library.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

MS 2192

GIVEN 2 CONCENTRIC AND PARALLEL EQUILATERAL TRIANGLES WITH THE AREA BETWEEN THEM DIVIDED INTO 3 EQUALLY SHAPED TRAPEZOIDS; COMPUTE THE AREA BETWEEN THE 2 TRIANGLES AS THE SUM OF THE AREAS OF THE 3 TRAPEZOIDS; SCHOOL TEXT

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, 19th c. BC, 1 tablet, diam. 7,1x2,5 cm, 8+3 lines in cuneiform script, drawing of 2 concentric and parallel equilateral triangles with the sides given as 60 and 10.

Commentary: The sides of the trapezoids are correctly computed. The text may have been an assignment to a student, but the answer to the problem is not given. No parallel to this text has been published before.

Published: To be published by Jan Friberg in the Manuscripts in The Schen Collection series, ed. Jens Braarvig.

Historical and Literary letters

LETTER TO KING SHULGI FROM A HIGH OFFICIAL NAMED IRMU OR ARADMU HAVING BEEN SENT TO A PROVINCE TO ENSURE THAT THE LOCAL GOVERNOR, ABA-ANDA-SA, WAS ACTING ACCORDING TO INSTRUCTIONS SENT TO HIM, REPORTING BACK THAT THE GOVERNOR WAS ACTING LIKE AN INDEPENDENT KING; AND THE REPLY FROM KING SHULGI TO IRMU, 2095-47 BC, COPY DATED 9TH MONTH, 5TH DAY, YEAR SAMSU-ILUNA THE KING AT THE COMMAND OF ENLIL

MS in Neo Sumerian on clay, Babylonia, 28th regnal year of King Samsu-iluna, 1722 BC, 1 tablet, 10,5x7,1x2,7 cm, single column, 29 lines in cuneiform script by Marduk-mushallim.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1996, yellow cloth gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Context: A belle lettre to King Iter Pisha of Isin, see MS 2287.

Commentary: This correspondence had become belles-lettres, 8 letters are published. The present one is unpublished.

Lexical texts

LEXICAL LIST OF TREES, WOODEN OBJECTS, GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES AND TYPES OF SPADES

MS in Sumerian on clay, Sumer, Uruk III, 3100-3000 BC, lower 1/2 of a tablet, 10,5x24,5x4,5 cm (originally ca. 25x24,5x4,5 cm), 9 columns, 120 lines in pictographic script.

Commentary: This is by far the largest pictographic tablet known. It represents a new lexical tradition different from the 13 Uruk lists of titles (MS 2429/4), animals, fish, plants, jars, cities, etc. The present list would have had no less than 230 geographical names compared to the Uruk city list of 88 entries. The later Tell Abu Salabikh (ca. 2500 BC) and Ebla (ca. 2400 BC) lists had 289 entries, but entirely different from the present one.

See also MS 2429/4 , Lexical list of titles, Sumer, 31st c. BC

See also MS 2340 , Lexical list of harp strings, Sumer, 26th c. BC

LEXICAL LIST OF BIRDS, ANIMALS AND OBJECTS, PRECEDED BY NUMBERS, 'THE TRIBUTE'

MS in Sumerian on clay, Sumer, ca. 2500 BC, 1 tablet, 12,6x13,4x2,5 cm, 6 columns, 96 compartments in a fine professional cuneiform script.

Binding: Barking, Essex, 1998, blue quarter morocco gilt folding case by Aquarius.

Commentary: 'The Tribute' dates to ca. 2900 BC; the present tablet is an Early Dynastic version of the text, the only one so far attested.

See also MS 3030 , Lexical list of buildings, Assyria, 681-669 BC

See also MS 1816, Isidorus Hispalensis: Etymologiarum sive originum, Germany, ca. 800

Medical texts

DIAGNOSES OF MEDICAL CONDITIONS WITH PROGNOSES OF THE OUTCOME, SUCH AS:

IF A MAN'S EPIGASTRIUM IS LOOSE, HE IS IN A CRITICAL STATE.

IF A MAN'S EYELIDS THICKEN AND HIS EYES SHED TEARS, IT IS A 'BLAST OF THE WIND'.

IF A SICK MAN IS RELAXED DURING THE DAY, BUT FROM DUSK HE IS SICK FOR THE NIGHT, IT IS AN ATTACK OF A GHOST.

IF A SICK MAN'S ADAM'S APPLE IS LOOSE, HIS SINEWS ARE DISEASED AND HIS NOSTRILS CLOSED, HE IS IN A CRITICAL STATE

MS in Old Babylonian on clay, Babylonia, ca. 1900-1700 BC, 1 tablet, 10,4x7,8x3,2 cm, 45 lines (originally 66) in cuneiform script.

Commentary: Medical texts of this category are well known from Neo Babylonian literature, while from the over 1000 year older, Old Babylonian period, few survive. Many of the Babylonian diagnoses and prognoses still hold true in modern medicine.

IF A YOUTH WHO HAS NOT KNOWN A WOMAN SUFFERS A PROLAPSE OF THE RECTUM, YOU CRUSH A ... AND A ... AND YOU HAVE HIM DRINK IT IN BEER, AND/OR MASSAGE HIM WITH IT IN OIL. IF IT IS NOT RELIEVED BY POTIONS OR SALVES, IF IT IS HIS RIGHT TESTICLE APPLY HEAT TO HIS LEFT SHOULDER BLADE; IF IT IS HIS LEFT TESTICLE, APPLY HEAT TO HIS RIGHT SHOULDER BLADE.

IF A YOUTH WHO HAS NOT KNOWN A WOMAN SUFFERS A PROLAPSE OF THE RECTUM, YOU BOIL UP A LIZARD; HE DRINKS THE FLUID AND HE WILL RECOVER.

IF A YOUTH WHO HAS NOT KNOWN A WOMAN SUFFERS A PROLAPSE OF THE RECTUM, YOU SIT HIM UP TO HIS WAIST IN STALE FINE FLOUR AND WHEAT FLOUR IN A ... OF ... SESAME, AND HE WILL RECOVER.

IF A YOUTH'S TESTICLES ARE INFLAMED, YOU MIX TOGETHER EQUAL QUANTITIES OF POWDERED ROAST BARLEY, AND POWDERED ...; IF IT IS SUMMER YOU KNEAD IT IN KASU-JUICE; IF IT IS WINTER, IN HOT WATER.

IF A YOUTH'S TESTICLES ARE INFLAMED, YOU 'IT IS BROKEN' IN HOT WATER WHICH ...; YOU ANOINT HIM WITH OIL; YOU REPEAT THIS FOR 10 DAYS. YOU REPEAT THIS FOR 20 DAYS AS WITH INFLAMMATION OF THE INTESTINES, AND HE WILL RECOVER.

IF A YOUTH SUFFERS FROM PROLAPSE OF THE RECTUM, YOU BOIL UP ... ..., UP TO HIS ANUS; HE SHOULD SQUAT DOWN, AND ... IN FRESH CRESS, YOU WASH IT IN WATER, STEEP IT, AND AFTERWARDS CRUSH FINE, AND MIX IT UP WITH THE CRESS; YOU BANDAGE AS A POULTICE WHEN HOT TO THE ANUS AND 'IT IS BROKEN' -.

IF A YOUTH'S HIPS HURT HIM, OR HE SUFFERS FROM STRANGURY, OR HIS KIDNEYS HURT HIM, OR HIS ... ARE INFLAMED, OR HE CANNOT SIT(?) DUE TO HIS ..., OR HE IS BLOATED WITH WIND, OR A TENDON IN HIS HIP, OR TESTICLE, OR HIS -

MS in Babylonian on clay, Uruk, ca. 300 BC, 1 tablet, 7,4x5,8x2,3 cm, 31 lines in cuneiform script by one of the leading Uruk scribes, Anu-Iksur or Iqisha.

Context: Other medical tablets are MSS2670and 3277. This tablet is written by a member of the well-known families of leading Uruk scribes, such as Anu-iksur or Iqisha. The excavations at Warka have produced whole archives of medical, magical and scholarly texts in identical script and format. The present tablet must come from one of those archives. All the other texts from this archive are now in international museums. Thus it must represent the work of one of Mesopotamia's leading medical practitioners of the late 4th c. BC.

Commentary: Part of the text is quite new, and part duplicates, restores and even clarifies a medical text from Assurbanipal's library.

The text has some very unusual contents, with both unusual words and interesting ideas. The first recipe treats a problem that appears on one side of the body with an action to the other side. This peculiar Mesopotamian concept first makes its appearance in a pre- Hammurabi medical text that treats toothache, and also in some later cuneiform cures for nose-bleeds, and may be interpreted as illustrating an underlying philosophy. The action in the present instant is the application of heat, which is not known in any other medical tablet, but which we now know, may have therapeutic benefit.

There is also an interesting procedural parallel with certain therapeutic recipes in Aramaic in the Babylonian Talmud. The vehicle prescribed here for applying the medicament varies according to the time of year; i.e. in summer it should be administered cold, in a kind of juice, but in the winter it must be steeped in hot water. Exactly the same point occurs in the Talmud, implying that this, and other curative procedures, have their roots in the more ancient Babylonian praxis.

Twice the scribe has written the signs he-pi in very small script, once on the obverse, and once on the reverse. The literal meaning of this expression is 'it is broken', and it serves to indicate that the medical tablet from which he was copying these recipes was itself fragmentary or damaged in certain places, implying that it was, even then, a recovered text of some antiquity. This is a very revealing point. It is clear that in both instances there is a word or two missing in the received text. The first is some element of materia medica, so we cannot be sure what it was, but in the second case, it is quite evident that the missing words at the end of the recipe must have been '... he will get better.' It must have been entirely obvious to the scribe himself. Nevertheless, his deep-seated reverence for traditional textual sources and the nature of his training meant that as a copyist, his responsibility was only to transmit the text as received, and not to add to it, or improof it, or even restore it.